Monday, December 29, 2008

Do Not Forget

i am grateful that i hold someone in my heart whose rage is articulate.

i ask that as we hold everyone in Gaza in our hearts we remember this poem by June Jordan:

Apologies to All the People in Lebanon

Dedicated to the 60,000 Palestinian men, women and children who lived in Lebanon from 1948-1983

I didn't know and nobody told me and what

could I do or say, anyway?

They said you shot the London Ambassador

and when that wasn't true

they said so

what

They said you shelled their northern villages

and when U.N. forces reported that was not ture

because your side of the cease-fire was holding

since more than a year before

they said so

what

They said they wanted simply to carve

a 25 mile buffer zone and then

they ravaged your

water supplies your electricity your

hospitals your schools your highways and byways all

the way north to Beirut because they said this

was their quest for peace

They blew up your homes and demolished the grocery

stores and blocked the Red Cross and took away doctors

to jail and they cluster-bombed girls and boys

whose bodies

swelled purple and black into twice the original size

and tore the buttocks from a four month old baby

and then

they said this was brilliant

military accomplishment and this was done

they said in the name of self-defense they said

that is the noblest concept

of mankind isn't that obvious?

They said something about never again and then

they made close to on million human beings homeless

in less than three weeks and they killed or maimed

40,000 of your men and your women and your children

But I didn't know and nobody told me and what

could I do or say, anyway?

They said they were victims. They said you were

Arabs.

They called your apartments and gardens guerilla

strongholds.

They called the screaming devastation

that they created the rubble.

Then they told you to leave, didn't they?

Didn't you read the leaflets that they dropped

from their hotshot fighter jets?

They told you to go.

One hundred and thirty-five thousand

Palestinians in Beirut and why

didn't you take the hint?

Go!

There was Mediterranean: You

could walk into the water and stay

there.

What was the problem?

I didn't know and noboby told me and what

could I do or say, anyway?

Yes, I did know it was the money I earned as a poet that

paid

for the bombs and the planes and the tanks

that they used to massacre your family

But I am not an evil person

The people of my country aren't so bad

You can expect but so much

from those of us who have to pay taxes and watch

American TV

You see my point;

I'm sorry.

I really am sorry.

***********************************************************************************

Throughout her career June Jordan was punished by the US publishing establishment for her refusal to be silent about Isreali aggression against Palestinians and the anti-Arab dehumanization that characterized US foreign engagement with the Middle East. People said she was alienating herself by taking this issue so personally.

I take it personally.

Modelling the form of transnational feminist solidarity that we must aspire towards, June Jordan famously said "I was born a black woman, but now am become Palestinian."

I take it personally that CNN says that Isreal is at war with Hamas, both because it uses the name of an organization to obscure the fact that this attack is launched against the Palestinian people. CNN, like the Israeli state, refuses again and again to even admit that there is such a people as the Palestinian people, that there is such a place as occupied Palestine. This is how genocide works, and I take it personally. I take it personally that in this age a "war" is no longer defined as a military engagement between two nation-states, that we can use the word "war" to describe what an occupying force, in the form of an apartheid state does to the people it has captured in a concentration camp. I am outraged that the only thing we can call for is a cease-fire, as if there is balance. As if these two entities have ever been equal. As if the United States has not been sending most of it's (our) international aid to buy weapons and build walls for the aggressor, the Israeli State. As if the more than 300 Palestinian people killed were equal to the one Israeli person caught by a missile that Hamas launched AFTER 30 missiles hit Gaza.

Would our strategy be to ask for a cease fire between the MOVE organization and the Philadelphia police? Would our strategy be to ask for a cease fire between the Black Panther Party and co-intel pro. "Cease-fire" is a belated and non-sensical term when the resources, the forms of weapons, have already been alloted so disproportionately.

I have a slingshot. When they come for me with a tank will you ask for a cease-fire, ask both sides to calm down?

I am taking this personally. I am not going to calm down.

All you have to do is remember that Palestinians are people like any other people, full of love and hope and beauty and brilliance who can be hurt, even while surviving occupation, racism, attacks against every one of their institutions and the unjust loss over and over again of the lives of their loved ones, of the homes of their skins, of the disrespect of being called out of your name and exiled in your own land again and again. All you have to do it remember that Palestinians are people and the absurdity and tragedy of this situation will fall on your heart and crush it, like mind is crushed today.

But the mass media is asking you to forget, with every word choice transmitted over here about what is going on in occupied Palestine right now. Asking you to forget that simple truth that even without a state (i would say ESPECIALLY without a state) people are people: full of love and priceless.

June Jordan's incisive repetition of "They said/they said so/what" in her poem is an illustration of what we are still being told today. The words of the Israeli state get credit (like the massive amounts of weapon-buying aid that we send them...on credit that they will never have to repay) and when their weak arguments for self defense against a group of people that they have forced into a cage prove to be lies, our media turns away.

All we have to do it to remember that there is no justification for genocide and we will see clearly what justice is. But our media is asking us to forget. Our 60th Anniversary of the State of Israel attending President and our "hail the great state of Israel" President-elect are asking us to forget.

Do not forget.

Sunday, December 28, 2008

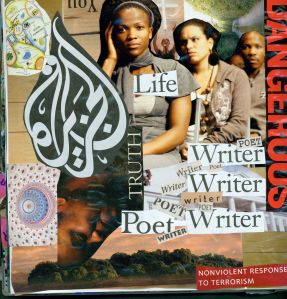

Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind!

Due to the huge and affirming response to BrokenBeautiful Press's Summer of Our Lorde we are THRILLED to present the Eternal Summer of the Black Feminist Mind, a portable progressive series based in Durham North Carolina in partnership with SpiritHouse, Southerners on New Ground, UBUNTU, the Land and Sustainability Working Group, Kindred Healing Justice Collective and more.

In 1977 the Combahee River Collective wrote a key black feminist manifesta groundbreaking in it’s assertion that the “major systems of oppression are interlocking. You are invited to the first session on the groundbreaking black feminist document The Combahee River Collective Statement. Download it at www.blackfeministmind.wordpress.com

and check out some radical exercises at www.combaheesurvival.wordpress.com

In Durham we'll be discussing it on January 7th. Email brokenbeautifulpress@gmail.com for details and feel free to read along wherever you are and comment here!

See you (t)here!!!!!

Thursday, December 18, 2008

Monday, November 10, 2008

Mere Relative: Audre Lorde, Grenada and the Ethics of Diasporic Solidarity

This is a paper that I presented (next to my beloved sister Zachari Curtis!) on a panel called "Radical Black Feminist Literatures" at North Carolina Central University's conference on "New Approaches to African Diaspora Studies." It is important for me to note that there were a WIDE range of definitions of diaspora in room...some more nostalgic, narrow and patriarchal than others. This is the seed of an upcoming chapter called "Diasporic Reports" so feedback is much appreciated!

love,

lex

Mere Relative: Audre Lorde, Grenada and the Ethics of Diasporic Solidarity

“Grenada is their country. I am only a relative.”

“To the average Grenadian, the United States is a large but dim presence

where some dear relative now lives.”

-Audre Lorde “Grenada: an Interim Report”

What kind of intimacy do I want to create here? Who do I imagine you to be anyway? Who would you have to be to understand what I am compelled to say here? Maybe you are black, because we are convened at an historically black institution. Maybe you know something about dispossession, and segregation and how the spaces you think you own are really part of something big and uncaring, like the state. Or an economy where black already means something that we didn’t consent to. Maybe you will understand, because you came here to talk about the African diaspora. Maybe you consider me your people. I pray to the Lorde of my choosing (Audre Lorde), that I am your people somehow, that my presence grows a space in your heart beyond understanding for love. But there is no one you can be that will guarantee that I make sense to you today. What kind of intimacy do we need? What kind of distance are we afraid of?

Can I be honest with you? I came here today seeking home. Six months ago I went Grenada seeking the same thing. And I found it in a way. The generous attention in your faces. The small island plants, smell of sea wind of embrace that felt familiar for a girl grown and summered on a different small island with a different economy. Does that make me sentimental? Audre Lorde, a black feminist lesbian warrior mother poet teacher born in Harlem says:

“The first time I came to Grenada I came seeking “home,” for this was my mother’s birthplace and she had always defined it so for me.” I will always believe that Audre Lorde was and is a woman and a spirit of rare brilliance, bravery, eloquence and insight. But this is a typical statement for a US born black person with Caribbean parents. Home for an Afro-Caribbean family, is not the United States of America. The harder lesson to embrace is that no where else is home either. This is about the double diaspora. Afro-diasporic people dispersed again by the market, out of the Caribbean and into the United States, or Canada, or Europe. Carrying the traces of colonialism and neocolonialism in over stuffed bags. And that’s not the heaviest baggage. Audre Lorde went to Grenada seeking home. But she could not find it. First, because of the cruelty of space and time, the stories her parents raised her with about Grenada were inevitably dated and referred to a place that no longer existed, and that place, overwritten with longing, may have never existed except in their memories. And on her second visit Grenada could not be home, could not be properly claimed by any black person because of the 1983 United States invasion into what was the first black socialist republic. Home, a place controlled by black people that refuses capitalism (or maybe that’s only MY definition of home) is a dream place, to dangerous to exist. As Lorde says: “What a bad example, a dangerous precedent, an independent Grenada would be for the peoples of Color in the caribbean, in Central America, for those of us here in the United States.” But that doesn’t mean what Audre Lorde found in Grenada, what I found years later was not familiar.

Grenada though not home, was familiar, because the US invasion of Grenada was justified by a logic that black people living in the US knew all too well. Lorde explains that racism is the primary export from the United States to the world. Here is her inventory: “The lynching of Black youth and shooting down of Black women, 60 percent of Black teenagers unemployed and rapidly becoming unemployable, the presidential dismantling of the Civil Rights Commission, and more Black families below the poverty line than twenty years ago—if these facts of American life can be passed over as unremarkable, then why not the rape and annexation of tiny Black Grenada?” Familiar, but not home.

Diaspora is not what I wish it was. Home in every black face and every majority black space on the planet. A fabulous circle of homegirls holding hands across continents, a way for me to look at you and know you know what I mean. Diaspora is not what I wish it was a strain that lets me trace my presence backwards across centuries like a fated journey an inevitable victory. Diaspora is not what I wish it was, but I am connected to you somehow. We are, despite it all, related.

And let me pause here before and inside of your affirmation to tell you what I do not mean. I do not consent to the definition of diaspora that says the African diaspora is sperm trailing across time from a far away mother land to a group of linked children. It’s not what you wish it was. Diaspora is not some true race legacy for us to hold on to. A story for the fatherless that tells us who and where and what and why our fathers are. Diaspora is not that. Diaspora is what makes that impossible. I do not consent to a fairy tale that leaves me in chains and then pretends those chains are not there. Diaspora is not Marcus Garvery reborn 50 times out of the womb of any black woman as long as she is black enough. You mean it well, but I’m not with that. As Brent Edwards reminds us, there is a difference between pan-africanism and diaspora. Who do you have to be to understand what I am trying to say here? Maybe you are black. Which could mean your mother was black, your children are gonna be black, which could have led you to believe, understandably that race is something we reproduce with our bodies. You know, over time, diaspora.

I am here to tell you (in the name of the Lorde no less), no. We do not reproduce race with our bodies. The only thing our bodies make is love. The only thing that rightfully lives in our skin is life’s longing for itself. The only thing that our bodies know how to make untaught is love and more love and more love. Because love is the only thing we need. If there was a contents label on my body it would say this person is made of some certain amount of water, which is another name for love, and a certain amount of cells remaking themselves, love. Love is the only thing I have, the only thing I have the RIGHT to make. And that’s what I’m doing here. And because I love you, I am going to be as honest as I can be.

Race is not something we make with our bodies. Race is merely something we survive. Only racism can make and remake race over time. And racism is a story about who can be killed. But that story, does connect us. So black people in the United States, Audre Lorde argues, in an urgent interim report that she stopped the presses on her own book to include...black people in the United States are related to black people in Grenada. But not because of our melanin or the blood in our veins, but because of racism, our killability, we are related by the blood that spills out. Black people in the United States are related to black people in Grenada because the United States is using the story of racism to steal power from all of us. Black people everywhere are related. Kind of like family. You know a group of people you are stuck with for better or for worse, tied to by law and survival, and that doesn’t mean there is love there, but there could be.

Audre Lorde models the practice of how we can relate to our dear relative, our mere relatives, our not very near relatives with love. And the first requirement is that we are honest about the fact that we are not all the same. Black people in the United States paid taxes that funded a military invasion into Grenada, and it was of course, disproportionately black people in that army through which the US invaded Grenada killing the young revolutionaries and imposing an economic situation that among other things caused people living in an island full of trees that produced cocoa beans to IMPORT chocolate. My uncle, who was in the Army at that time wanted so bad to go to Grenada, years and many books later he is glad he didn’t get his wish. But directly or indirectly the same imperialist racism that makes black people in the United States related to black people everywhere, consistenly puts us on opposite sides, of a very dirty coin. As blacks in the US we consent over and over again to violence against other black people done in our name, and usually without our knowledge. Not a very brotherly situation at all.

Audre Lorde is saying, as a mere relative, that it doesn’t have to be that way. We are related through racist systems that we do not control, but we can only look each other in the eye, with love, if we acknowledge our different relationships of power. Who does it benefit when my own oppression here overshadows my privilege in relationship to the people living in places that this country has invaded through the racist ideology of the war on terror. Does diaspora now mean that I am related to Iraqis to everyone in Guantanamo through systems of racism. And if so, how can I be related to those who racism oppresses through intentional solidarity, the practice of love? What kind of intimacy am I trying to create here? I think as we innovate in our study and practice of black diaspora our key concern needs to be the terms under which we are related and the ways the and privileges that our different relationships to power and access make us accountable. Diaspora, I would argue must compel us towards what Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Mohanty would call a democratic transnationalism, where not only our skinfolks become our kinfolks, but where we are accountable to everyone oppressed by racism with a strategic solidarity that acknowledges the systems through which we meet each other. Familiar, and struggling, mere relatives, until we can meet, at home.

Monday, November 03, 2008

For My People: Freedom in Durham

So because I live in Durham I get to be inspired all the time by the brilliance and creativity of people. Not all the brilliant and creative people in the United States live in Durham, it just feels that way sometimes. Like today when a black woman who is a doctor and a mother of 6 came to speak to the Durham School Board and the Durham Public School administration about why students should be able to choose educational alternatives. Or like right now when Durham's Youth Noise Network is broadcasting a voice recording of June Jordan's "On the Night of November 3rd 1992" about the end of the (first) Bush era and speaking about their views on electoral politics.

So I write about Durham...as often as possible...because people act like they don't know about the resilient, resourceful miraculous people living, working and loving here. I wanted to share two examples with you all that are in cyber and book form right now.

First..check out an article I wrote called "The Life of A Poem: Audre Lorde's 'A Litany for Survival' in Post-Lacrosse Durham" for an online journal called Reflections: A Journal of Writing, Service Learning and Community Literacy. It's in blog format so you can post comments..I hope you do!!!!

And THEN....(I am even more excited about this one) get/find/borrow a copy of Abolition Now!: 10 Years of Strategy and Struggle Against the Prison Industrial Complex just out from AK Press!!! This is a book collaboratively edited by the awesome publications committee of Critical Resistance and it features a chapter I wrote called "Freedom Seeds: Growing Abolition in Durham, North Carolina."

I'm so lucky that I get to live here and be inspired by you!!!!!!

love,

lex

Monday, October 27, 2008

Thus Saith the Lorde

an artifact for survival...

History is not kind to us

we restitch it with living

past memory forward

into desire

into the panic articulation

of want without having

or even the promise of getting.

And I dream of our coming together

encircled driven

not only by love

but by lust for a working tomorrow

the flights of this journey

mapless uncertain

and necessary as water.

-Audre Lorde

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

Until...

I'm a fan. (Can you tell?)

As an outgrowth of the collaborative online community transformation venture Queer Renaissance (www.queerrenaissance.com), and a compelling poetic filmic vision, Julia Wallace is creating Until, a poem crystallized into a short experimental narrative film about friendship, love, secrecy, shame and the possibility of freedom. And I want you to know about it. Because I love you.

After hearing the poem and reading the screenplay for Until I already have a crush on the main character. Pro, a quiet loving earnest college student wants the best for her best friend Hailey. And she's thrilled and gratified when after facing rejection from some guy on campus, Hailey wants her. As always though, it gets complicated when the lights turn on. What will it take for each woman to be true to herself in private and in public?

Y'all, reading this screenplay makes me want to be a better braver person. It scrapes up those moments when we choose our fears over each other, and when we choose each other out of fear...it makes me want to build altars and monuments to those public hand holdings and private yeses that risk everything except our integrity. And to those moments when we almost get there.

There should be a billion films like this, but there aren't, and Julia and the crew are shooting November 14-16 in Atlanta so go here to find out more about Until and how you can support that necessary process of making our love, our questions, our hope and our process visible and tangible.

love always,

lex

Sunday, October 19, 2008

Because All Our Love Matters: State Economic Violence and the Beauty of Survival

Conference on the Care of Dependent Children: Call for the Conference, Theodore Roosevelt (1908)

Social Security Act of 1935: Title IV-Grants for Sate Aid to Dependent Children (1935)

Social Security Act Amendments of 1939: Old Age and Survivors Insurance Benefit Payments (1939)

"Cleveland Sends 9 Negroes South" New York Times, June 9, (1956)

Illegitimacy and Its Impact on the Aid to Dependent Children Program, Bureau of Public Assistance, (1960)

The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, Daniel P. Moynihan (1965)

"Woman Battles Sterilization Ruling," Harry Trimborn Los Angeles Times, May 31 (1966)

"47 More Negroes Held in Carolina," James T. Wooten, New York Times, November 13 (1968)

Dandridge vs. Williams, Supreme Court (1970)

"Welfare is a Women's Issue," Johnnie Tillmon (1972)

"States Abortion Law Helps Reduce Welfare Costs," Oakland Tribune, (1972)

Hearings on Health Care and Human Experimentation, Niel Ruth Cox (1973)

"Funding Sterilization and Abortion for the Poor," Sheila M. Rothman (1975)

"State of the Union Address," Gerald Ford (1976)

"Restoring the Traditional Black Family," Eleanor Holmes Norton (1985)

(All of the above can be found in Welfare: A Documentary History by Gwendolyn Mink and Rickie Solinger)

Welfare's End, Gwendolyn Mink, (1998)

Still Lifting, Still Climbing: African American Women's Contemporary Activism, Kimberly Spinger ed., 1999

especially:

"Vision Statement", National Black Women's Health Project

"'Triple Jeopardy': Black Women and the Growth of Feminist Consciousness in SNCC, 1964-1975," Kristin Anderson-Bricker

"'Necessity Was the Midwife of Our Politics': Black Women's Health Activism in the 'Post'-Civil RIghts Era (1980-1996), Deborah R. Grayson

Beggars and Choosers: How the Politics of Choice Shapes Adoption, Abortion and Welfare in the United States, Rickie Solinger, (2001)

Soul Talk, Gloria Hull (2001)

Women of Color and the Reproductive Rights Movement, Jennifer Nelson (2003)

The Politics of Public Housing: Black Women's Struggles Against Urban Inequality, Rhonda Y. Williams, 2004 (and props to Rhonda for suggesting most of this reading list)

and

Faubourg Treme (www.tremedoc.com)

www.hermanshouse.org

www.maryturner.org

www.miamiworkerscenter.org

www.poweru.org

www.takebacktheland.blogspot.com

www.jessemuhammed.blogspot.com

www.2-cent.com

and especially Prisons as a Tool for Reproductive Oppression: Cross-Movement Strategies for Gender Justice

Remarks of Gabriel Arkles from Sylvia Rivera Law Project on panel at CR10, 9/27/08

let me start with an excerpt from an email I wrote the other night:

predictably, becoming a 48 hour expert on welfare in the US has made me really really angry.

it's crazy how brutal and extreme the implications of US welfare policy are. the whole set of laws and the political speeches that endorse them are written to make black motherhood a crime and to make the production or sustenance of black life false value, unvalue, negative possibility.

like the federal government funding sterilizations at a 90% rate and abortions only at the rates that the states do (so at the most 50% in the 1970's

or this woman literally going in to jail because she refused to undergo a sterilization she was sentenced to in court for the minor charge or being in a room where she knew marijuana was being consumed.

never meant to survive. never even meant to be born.

but then the miraculous thing is how we keep doing both those things anyway, persistently reborn regardless...

like Martha Benton a black mother who as the leader of a second generation of black women organizing for their right to public housing in Baltimore says of her mentor Goldie Baker "I am her creation."

and like the sisters at what was National Black Women's Health Project and Sister Care and other sustainable health collectives for black women saying "necessity was the midwife of our politics"

and like the women who founded the Georgia Hunger Coalition who I literally saw chant down the evil EBT/food stamp policy makers at the Jimmy Carter Library when I was 18

and like Rosemarie Mitchell at Low Income Families Fighting Together who told me last weekend that her 7 years working for LIFFT is the pursuit of happiness made real even though she cries late at night sometimes

or like Paul Newman, one of my students/adopted siblings who read a poem to a crowd tonight while shaking from nervousness and the chill in the air about how the school to prison pipeline is doing everything to steal his life but how he's a superhero so it can't destroy him.

So anyway. I'm gonna be here tonight writing about it.

because all our love matters,

lex

All our love matters. Neoliberalism be damned.

My reading up on welfare policy and politics in the United States has me wishing I was reading slave code instead.

We have all heard the myth of the welfare queen, having babies 5 or 6 IN ORDER to be poor enough to steal assistance from the government. Some of us have heard that myth over and over again for decades. That is the myth that allowed politicians (most notably Reagan and Clinton) to screw over poor women and children of all races in the United States over by dismantling welfare piece by piece. Somehow repetition got voters to believe that most of the people on welfare to believe that some scandalous black woman with a brood of kids was the typical welfare recipient. To forget that most of the people on welfare have always been white and that (according to the Bureau of Public Assistance itself) only half of one percent of mothers on welfare even have more than 5 kids. And, according to government stats again, most mothers on welfare don't have any kids while they are on welfare and the overwhelming majority of mothers on welfare only have one or 2 kids at all.

But somehow we are all told this story. Poor black young women have kids to cheat money from the US government. Which means that poor black children (and poor children generally) are not only worthless, they create negative value and negative values at the same time. How dare these black women pretend tha the lives of their children are valuable enough to make their survival a community concern. The nerve.

Of course we are hearing the same story about the children of immigrants now. People are coming to the United States to have their children in order to steal benefits, cheating into a citizenship that was never meant to value the lives of the children of those forom the countries that the United States destablizes for economic gain.

This mundane every day set of racist stories teaches, and makes normal the most deadly, inhumane and disgusting lie that has ever been told:

Some lives are worth less than nothing. At birth.

Which of course means, some people should be prevented from being born.

If the denial of benefits to children in need wasn't disgusting enough to someone reading this, please remember that these policies are in bed next to the targeted prevention of certain people's lives from the outset. Gary Bauer, chief aide to Ronald Reagan (who by the way along with all of his other crimes against humanity Reagan is the person who coined the term "welfare queen") blamed the "reckless choices" of poor women who had children the cause of an apocalypse "There will either be no next generation, or there will be a generation that is worse than none at all." Representative E. Clay Shaw of Florida agreed arguing that poor women be sterilized "when they start having these babies one after another, and the terrible thing they are doing to the next generation...something has got to be done to put a stop to it."

What does that mean? "Worse than no generation at all." Whose life is worse than the absence of life on the planet? What does it mean to prefer the end of humanity to a future in which the children of poor women exist?

And everything possible was done. When Georgia and North Carolina and Florida et al failed to make compulsory sterilization a requirement for women receiving welfare, California led the move, first a jusdge sentences a woman on welfare to sterilization for a minor infraction. And the federal goverment when slick institutional violence style, using imbalanced funding to make sterilization more accessible to poor women than abortion. (see Funding Sterlization and Poor Women citation above---i wish it was just a conspiracy theory, but it's not.)

And reading all of this, I was sickened, but not surprised. As Gabriel Arkles points out prisons have an explicit policy to govern the lives of transgendered prisoners in order to "prevent pregnancy" and we know that women who give birth in prison are often sterilized at the moment they give birth under anesthesia and very shady "consent" circumstances. The state, especially a state that has sold itself to neoliberal capitalism has every reason to prevent some folks from being born, some folks from parenting...because the values we create say life is everything, and all life is priceless, our autonomy of when and how we parent is ours, because we, queer, racialized, poor, immigrant radical parents and queer, racialized poor immigrant radical youth are creating a world that is valuable without the sale of people and the enforcement of really bad ideas.

And we are born and reborn again and again. So Bauer and Shaw and so many others are afraid of the world that we ARE creating...with our youth and our rebirth and our literal birth and all the other forms of our creativity.

Be scared. Shit.

Because we are born and birthing and just these past couple of weeks I met some amazing midwives of color like Ayanfe and Anjali and some amazing mamas of color and some amazing youth of color and especially some amazing organizers committed to survival, which is the resounding counter message that our lives mean everything

because all our love matters.

now.

always,

lex

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Hail the Birth of Quirky Black Girls Magazine!

Quirky Black Girls is a network of fierce black women. We share our dreams, visions, and thoughts with you by producing the feminist publication QBG (Quirky Black Girls) Magazine, a quarterly ezine focusing on politics, cultural criticism, and social change. QBG Magazine features our art, poetry, fiction and nonfiction, and our ruminations on popular culture and social issues.

mission

QBG Magazine aims to provide a forum for Quirky Black Girls - and those who love them - where feminist dialog is the only norm and following your truth is the the only rule.

QBG Manifesta

Because Audre Lorde looks different in every picture ever taken of her. Because Octavia Butler didn't care. Because Erykah Badu is a patternmaster. Because Macy Gray pimped it and Janelle Monae was ready.

Resolved. Quirky black girls wake up ready to wear a tattered society new on our bodies, to hold fragments of art, culture and trend in our hands like weapons against conformity, to walk on cracks instead of breaking our backs to fit in the mold.

We're here, We're Quirky, Get used to it!

.... Quirky Black girls don't march to the beat of our own drum; we hop, skip, dance, and move to rhythms that are all our own. We make our own drums out of empty lunchboxes, full imaginations and number 3 pencils.

Quirky Black girls are not quirky because they like white shit; rather they understand that because they like it, it is not the sole province of whiteness.

Quirky black girls are the answer to the promise that black means everything, birthing and burning a new world every time.

Sound it out. Quirky, like queer and key, different and priceless, turning and open. Black, not be lack but black one word shot off the tongue like blap, bam, black. Girl, like the curl in a hand turning towards itself to snap, write, hold or emphasize. Quirky. Black. Girl. You see us. Act like you know.

We demand that our audiences say "yes-sir-eee" if they agree and we answer our own question "What good do your words do, if they don't understand you?" by speaking anyway, even if our words are "bruised and misunderstood."

Quirky black girls are hot!

Whether you're ready to see it or not.

Quirky means rejecting a particular type of "value," a certain unreadiness for consumption and subsumption in an economy of black heterocapital. This means that Quirky Black Girls act independently of dominant social norms or standards of beauty. So fierce that others may not be able to appreciate us just yet.

No matter what age we are, we hold onto that girlhood drive for adventure, love for friends, independent spirit, wacky sense of humor, and hope for the future.

Quirky Black Girls resist boxes in favor of over lapping circles with permeable membranes that allow them to ebb and flow through their multiple identities.

Quirky Black Girls- Embrace the quirky!

Sunday, October 05, 2008

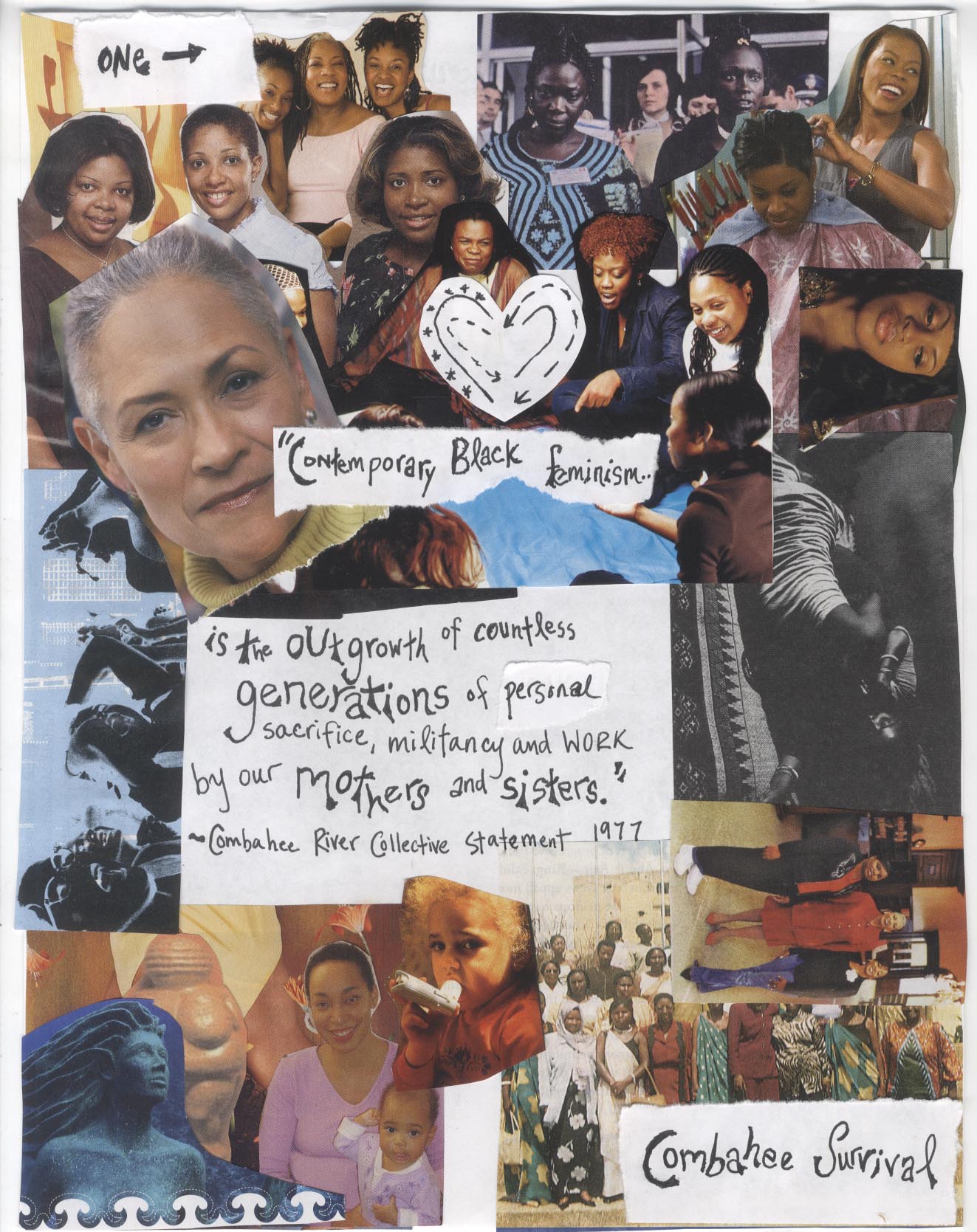

Combahee Survival

We were never meant to survive. None of us. We were never meant to find each other, love each other, remember the warriors that came before. We were never meant to know these histories. We were never meant to turn our trauma into a map for transformation. We were never meant to survive. But we do it anyway.

Break it down. Sur viv al. Life underneath waiting to embrace all of us. Survival is a poem written in a corner, found waiting in a basement, forgotten. Survival is when the timeliness of your word is more important than the longevity of one body. Survival is spirit connected through and past physical containers. Survival is running for your life and then running for Albany city council without consenting to the State. Survival is shaping change while change shapes you. Survival means refusing to believe the obvious. Survival means remembering the illegal insights censored in the mouths of our mothers. Survival is quilt patterns, garden beds. Survival means growing, learning, working it out. Survival is a formerly enslaved black woman planning and leading a battle that freed 750 slaves from inside an institution called the United States Military. Survival is out black lesbians creating a publishing movement despite an interlocking system of silences. Survival is a group of black women recording their own voices, remembering a river, a battle, a warrior and creating a statement to unlock the world. Survival is like that.

We were never meant to survive. And we can do even more. This booklet moves survival to revival, like grounded growth, where seeds seek sun remembering how the people could fly. We are invoking the Combahee River Collective Statement and asking how it lives in our movement now. And the our and the we are key to this as individual gains mean nothing if others suffer.

We were never meant to survive but we will thrive. We want roundness and wholeness, where everyone eats and has time to be creative has time to just be, What tools does it give that are necessary to our survival? What gaps does it leave us to lean into? Black feminism lives, but the last of the originally organized black feminist organizations in the United States were defunct by 1981.

Here we offer and practice a model of survival that is spiritual and impossible and miraculous and everywhere, sometimes pronounced revival. Like it says on the yellow button that came included in the Kitchen Table Press pamphlet version of The Combahee River Collective Statement in 1986 "Black Feminism LIVES!" And therefore all those who were never meant to survive blaze open into a badass future anyway. Meaning something unpredictable and whole.

We were. Never meant. To Survive. And here we are.

And beyond survival, what of that? In 1977 the Combahee River Collective wrote "As Black women we see Black Feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneuos oppressions that all women of color face." They also said "The inclusiveness of our politics makes us concerned with any situation that impinges on the lives of women, Third World and working people." And they concluded: "If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression."

Today we, a sisterhood of young black feminists, mentored in words and deeds by ancestors, elders, peers and babies, assert that by meditating on the survival and transformation of black feminism we can produce insight, strategy and vision for a holistic movement that includes ALL of us. So while this is a project instigated by self-proclaimed (and reclaimed) black feminists, our intention is that it can be shared and changed by everyone who is interested in freedom.

Check out the exercises, form a study group, and contribute to the Combahee Survival Zine at www.combaheesurvival.wordpress.com!

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Enough!

I think this is a great opportunity to engage in the much-needed and not so often had conversation about class within progressive movements. As I've told many of you...I believe that radical cross-class alliances are what it will take to effectively resist and dismantle capitalism forever. So let's go! I look forward to your comments, responses, and essays to be published in the near future.

much love,

lex

p.s. I have an article in here about the "Pedagogy of Debt"...let me know what you think!

Dear friends,

After much excited brainstorming, dialoguing, essay soliciting, and teaching ourselves basic web skills, we are thrilled to announce the official launch of a new website: ENOUGH!

ENOUGH is a space for conversations about how a commitment to wealth redistribution plays out in our lives: how we decide what to have, what to keep, what to give away; how we work together to build sustainable grassroots movements; how we challenge capitalism in daily, revolutionary ways.

We want this site to be a space for conversation, inspiration, and the creation of ideas. Please read, comment, send us thoughts, submit essays, and join the conversation!

Tyrone Boucher and Dean Spade

www.enoughenough.org/

Friday, July 25, 2008

The Forced Poetics of Black (Feminist) Publishing: Toni Morrison as Editor

This is the text of an essay my sista Zach is reading outloud on my behalf at the Toni Morrison Society Conference this weekend in Charleston, SC.

note:

Think about it. Have you ever had a chosen sister so who could co-write you a dictionary for the secret language of yes? Someone who lives in the growing part of your heart, reciprocally, so if I’m in Durham, she’s home, and if she’s talking to you I’m in your face? A sister true, so honest, so open and priceless that your brainwaves match her breath control even in front of strangers? Did you know it was possible to enjoy a faith that exceeds the limits of one body, because look. It’s happening. Now.

(Please email Alexis Pauline Gumbs at apg5@duke.edu with feedback or inquiries about this paper. And don’t blame the messenger for any shortcomings.)

I.

May we open with an artifact?

On October 27th 1975 Toni Morrison wrote a letter to June Jordan, the poet, on behalf of Random House, the publishing company, in regards to the possibility of publishing her poems:

“The answer they gave was ‘we would prefer her prose---will do poetry if we must.’ Now I would tell them to shove it if that were me—and place my poetry where it was received with glee. But I am not you. Nor am I a poet.”

Toni Morrison is not a poet. One thing that Toni Morrison learned in her many years working for New York City’s Random House publishing company was that the economy of publishing in the United States was in no way random. Especially not when it came to race. Despite her intimate knowledge of the constraints of the mainstream publishing, as an editor Toni Morrison made miracles. She words that were never meant to survive a way through to the future. Many of these have been the words I needed to survive up to this moment. The Library of America edition of James Baldwin’s Collected Essays, Toni Cade Bambara’s post-humously published novel (These Bones Are Not My Child) and short stories (Dream Sightings and Rescue Mission). It was Morrison, before she even published her own first novel, who pushed Ntozake Shange and Alice Walker into print. Often the difference between whether a particular book is or is not is print is literally whether or not Toni Morrison got involved. Without the diligence, strategy and vision of Toni Morrison there is no reason to think the category “Black Women Writers” would be teachable or even imaginable in the literary field.

Sometimes the depth and tactility of the worlds Toni Morrison creates in her novels lead me to believe that she is god. Such a conclusion would be unfair, to Morrison and to the rest of us, but it is fair to assert that Toni Morrison is and has been a major force in the world of black women’s publishing, and black publishing generally in the United States. This paper uses Morrison’s role as a key figure to focus an examination of two broad problems in the project black publishing oriented toward freedom: the problem of poetry and the problem of profit.

II.

(Black) Poetry is a problem in the American publishing market. (Publishing is a problem in the black market of poetry.) So I find Martinican theorist Edouard Glissant’s concept of forced poetics a useful analytic through which to examine the problem of poetry in the American market. For Glissant, the dilemma of the situation of forced poetics is a result of oppression. Everything the oppressed person says, in the language of their oppression, reproduces the situation of oppression because it comes from that same situation. Poetic right? In other words nothing we say is actually free from oppression, because we who are speaking are still oppressed. Even our mouths, our hands and the words we choose to toss towards one another.

I would argue that on the level of publishing, within a market, this is even more pervasive. How, in a capitalist market could you possibly publish something that does not consent to a capitalist system (even while appearing not to)? How in a dominant society that presumes and benefits from the unfreedom of black people could you publish poems by or for free black people?

June Jordan, the same difficult to publish poet we began with, had some ideas about this problem. In her essay “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America or Something Like a Sonnett for Phillis Wheatley” June Jordan illustrates the paradox thusly

“A poet is somebody free. A poet is someone at home.

How should there be Black poets in America?”

Elaborating on the impossibility of black poetry in a country that enforces illiteracy and homelessness for black people, June Jordan describes the existence of black woman poet Phillis Wheatley as a miracle. And if publishing a book of poems as a slave was difficult, Jordan mentions Wheatley’s lost second book of poems to assert that it would have been even harder to publish the poems of an independent black woman than to publish the poems of a slave.

Jordan says “I believe no one would have published the poetry of Black Phillis Wheatley, that grown woman who stayed with her chosen Black man....From there we would hear from an independent Black woman poet in America.

Can you imagine that in, 1775?

Can you imagine that today?”

What is June Jordan suggesting? Hold this in your imagination for a moment because I think it might be true.

The poems of the enslaved are easier to sell than the poems of the free.

And that’s if you can sell poetry at all. In Toni Morrison’s letter to June Jordan, the poet, she explained that the rejection of June Jordan, the poet, as a poet by the very strategic Random House was based on (quote) “a rudimentary capitalistic principle” prose is a commodity that can be sold, poetry, is something else. I agree with Random House on the distinction that they make between narrative form and poetry. Stories, novels and essayys as mind-expanding, affirming transformative and beautiful as they may be when in the hands of someone like Toni Morrison are still, contained when compared with poetry. Sylvia Wynter (yet another Caribbean theorist) defines the “poetic” as the way we create a world by trying and failing to describe a human relationship to an environment. Poetry is an unwieldy product because it never quite stops being a process. Poetry, as Sylvia Wynter defines it, is dangerous to capital because it challenges the presumption that human beings are related to each other and to their environment through a means of production, and through access to commodities. Poetry, thus defined, says maybe I’m related to you through a process of creation. Maybe we can’t buy or sell each other, maybe the fundamental shape of our relationship is the way my words fit in your mouth. Or vice versa. Who is Phillis Wheatley? What is black poetry after slavery?

How do you sell poetry by poets if a poet is a person not for sale?

III.

And who would you sell that poetry to anyway? The problem of profit in the mainstream publishing market is a primary determining factor in which books stay in print and which words become inaccessible to the future. How then, could one possibly be accountable to an audience of the rare, marginalized, silenced, undertaught, criminalized people we love? To be blunt: Is it possible to publish anything on a widescale in the United States that is not ultimately for white people with access to education and disposable book-buying money? Who cares if I have something to say to you?

In 1977 only two years after Toni Morrison’s realist letter to the poet June Jordan, the two writers were part of a New York based group of black women writers called the “Sisterhood” along with Alice Walker, Ntozake Shange and many others. These women envisioned an autonomous black women’s publishing initiative that would have been called Kizzy Enterprises. Kizzy Enterprises, which Ntozake Shange offered to house, in her house was intended to be a not for profit black publishing enterprise, which would keep important black texts in print, publish a periodical targetted to the black working masses and be supported, not by sales, but by the contributions of like-minded people. According to the minutes taken in the Sisterhood planning meetings for Kizzy Enterprises Toni Morrison made it very clear that none of the plans for Kizzy should be mentioned to Random House. Evidently Morrison understood black non-market publishing to incompatible with a mainstream publishing market in which she was still struggling to support black women writers. In the end Kizzy Enterprises was never born. A friend of ours asked Ntozake Shange about it the other day and she barely remembers the idea. I would never have known about it if June Jordan hadn’t kept the meeting minutes and if Harvard hadn’t kept June Jordan’s files. Kizzy remains an idea haunting the black presence in the literary market which remains determined by mainstream publishing interests.1

Somethings are never meant to survive. And sometimes they do. Because look at what is happening now. I choose to read this history as evidence that autonomous publishing oriented towards freedom is something that is still making. Among other reasons, this is because despite what she has to say, Toni Morrison is a poet.

May we close with an artifact?

In May 1985 Toni Morrison wrote an essay for the 15th anniversary issues of Essence Magazine. Cheryll Y. Greene, a genius and warrior who fought to publish towards freedom in the very confining pages of this black fashion and beauty magazine, created a Celebration of Black Womanhood, for this anniversary issue of Essence and asked Toni Morrison to provide some last words. Toni Morrison the poet addressed June Jordan retroactively and all of us with these last words and now we address her too:

“You had this canny ability to shape an untenable reality, mold it, sing it, reduce it to its manageable, transforming essence, which is a knowing so deep it’s like a secret. In your silence, enforced or chosen, lay not only eloquence but discourse so devastating that “civilization” could not risk engaging in it lest it lose the ground it stomped. All claims to prescience disintegrate when and where that discourse takes place. When you say “No” or “Yes” or “This and not that,” change itself changes.”

Thank you.

Monday, July 14, 2008

the half: (to alexis, in flight)

Wednesday, July 09, 2008

Thursday, July 03, 2008

Too Important or What We NEED: Transformation in the Face of Violence and Silence

"I wrote it because I wanted to talk abut blackwomanslaughter in a way that could not be unfelt or ignored by anyone who heard it with a hope perhaps of each one of us doing something within our immediate living to change to change this destruction."

"We are too important to each other to waste ourselves in silence."

- Audre Lorde in a prefatory essay to Need: A Chorale for Black Woman Voices

In 1979 Barbara Smith sent Audre Lorde a news clipping via snail mail. Yet another black woman in her community in Roxbury had been found dead. Over these four months, during which 12 black women were killed in the black nieghborhods of Boston, black feminists, led by black lesbian feminists built a coalitional movement to respond, using public art, poetry, self-defense, publishing and political education. Barbara Smith and Lorraine Bethel were editing what would become the foundation black feminist collection, Conditions 5: The Black Women's Issue. Audre Lorde wrote Need: A Chorale for Black Woman Voices in response to this wave of murders. The energy and analysis forged in the words and promises exchanged between black feminists at that moment grew into a broad movement that lives, waiting and growing in those of us hungry for the words that were never meant to survive.

This past Monday, not yet 30 years after Barbara Smith's letter to Audre Lorde, Moya sent an email with a link to a news story:

http://abclocal.go.com/wpvi

This woman is black

so her blood is shed into silence.

A building full of neighbors heard the screams of this survivor while she was being sexual assaulted in her home, but were at a loss to actually act against this violence in their community. They didn't know how to respond, they didn't want to believe what was happening. So they kept their doors closed. They went to sleep.

This story is important for a number of reasons. As Moya points out it is yet another instance of silence within the black community about violence against a black woman coming on the heels of Megan Williams, Dunbar Village, R. Kelley's Acquittal and more. This is what breaks our backs.

I also think this story, literal silence in the moment of violence, is important for what it demonstrates more generally. Our silence, as oppressed communities about the gendered violence that disproportionately impacts our communities is glaring, harmful, devastating. We generally really feel that in a racist police state, and individualist capitalist state, a fear-filled falling apart place we don't have the resources to respond to violence even when we hear it happening, on the news and in our buildings every night.

But if we have each other, we do have what we need to take care of each other, hold each other accountable, keep each other safe and whole. If we have each other we do.

And I say, thank the Lorde, we have in Need a resource for transformation and a means to open us these impossible conversations about the real costs of gendered violence in our communities. The task of the poet is to say the unsayable, and Audre Lorde, may she never be forgotten, literally gives us the tools to open our mouths.

The UBUNTU Artistic Respons committee which convened in Durham, North Carolina in the midst of the Duke Lacrosse Rape Case, used Need (in addition to other poems and the documentary NO! by Aishah Simmons) to break open rooms of people and to instigate real discussions about the impact of gendered violence against black women WITHIN black communities, at the hands of other black people.

When my father, a person professionally trained and personally prone to debate and argument read Need he had no arguments to make. He told me that reading the piece was simply a moment in his education. He compared it to a moment in high school when he watched a film that documented all the shaven hair, all the bodily ashes, all the teeth and bones of the victims of the Nazi holocaust. He said that a mass of violence, an unimaginable horror had become visible and real to him in Audre Lorde's words. He said there was no question about whether this was true, whether it was relevant, whether it impacted him. He said now I know. The only question is what we do.

This is the Summer of Our Lorde, when we transform silence into action and power. I want to ask us to read and share Need available for download via:http://letterstoaudre.wordpress.com/need-end-violence-against-women-of-color-now/

with everyone we can share it with. Let us read it with other women in our communities, let us print our copies and give them to our families. Let us build a fire of healing that can ignite our communities into the conversations we need in order to build the trust, connection and analysis that we need to work together for survival, safety and love in our communities.

love always (in the hands of Audre),

lex

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Afro-Futurity: Going On by Gnarls Barkeley

I'd love to know what this new music video for Going On by Gnarls Barkley makes you think of...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u_R9fId_Rqo

Kameelah Rasheed put me on to this video. I am first of all grateful for it. I love watching it. On the first 4 watches it seems to have a message yet to be revealed and unconcealed. I love the beauty of the people in the video, both in the choreographed movements and the way they are dressed which for me bring up today, the 1970's, tomorrow and beaded yesterdays still to be imagined. I love how the futurism of the video is not technological. I love the details of the door. I want to know that the circular dance that the people do in the first part of the video reminds me of. It reminds me of something I believe in and don't have a precise reference for. I wonder how skeptically Saidiya Hartman would look at me for relating to that music video africanized moment through the eye in my forehead for memory.

I love that the people are carrying the portal to the future in their hands. I relate to the way their exuberance transforms into fatigue. I am inspired by the way their fatigue becomes reverence. I love the words of the song, I love the way the words are highlighted strategically all along.

I wonder about what levels of love are meant and residing there in words that seem to be spoken by I man (but they say what I want to say). I wonder who the singer is speaking for. The video put the words into the mouth of the lead man, and projects them onto the sometimes smiling, sometimes pained, sometimes pensive face of the lead woman. I wonder if the words about there "being a place for you too" are for a lover, a gendered lover? a whole gender of us to be left behind while male explorers forge forward again? I wonder what it means for the words of the song to vascillate between telling the imagined person being sung to "I'll see you there" and "I'll miss you." The main questions of the video for me live with the woman distinguished half way in as the "lead woman." What divides her from the "lead man" what connects her to him? Their movements are similar, the framing of the video makes it seem that a love relationship connects them, but the words to the song, which seem to be about leaving someone behind while also projecting that person into the future seem to divide the two characters. Most explicitly the command "don't follow me" made in words that seem to come out of the portal doorway after the man jumps could be meant for the woman who follows and jumps through the doorway, just as athletically anyway. If the words come to the viewing audience from both of the jumpers...why are they timed between the two jumps? Is the woman actor or audience in this video.

And to what extent is she or is she not me? Imma be thinking about this for a while. I'd love to know what you think.

love,

lex

p.s. In related news...the reason my reading of this film is mediated by Saidiya Hartman is because (in addition to her brilliance and perpetual relevance to all my thoughts) even as I write this I am supposed to be revising my review of Hartman's Lose Your Mother for the special issue of Obsidian on Ghana...so any thoughts about Hartman's book would be much appreciated too!

Friday, May 16, 2008

Dear MaComere: Dream Come True

Yesterday, J, my number one comadre, insisted that I stall my strawberry picking adventure in order to cradle her for a 10 minute nap. Powerful woman that she is, spirit healer that she is, listener for another world that she is, I trusted that there was something divine in her whine. I waited. After the nap, our mailman knocked on our door with the first package that I've ever had to sign for since we've lived here. And inside were copies of the book you see above, the literary journal of the Association of Caribbean Women Writers and Scholars. MaComere. The word MaComere has no real translation into English...its translation into Spanish would be mi comadre. It is the way women in the French influenced Caribbean name the women who they grew up with, the woman who they tell everything. It means best friend, comrade, sister in everything. To say it literally we have to invent a much needed phrase "my co-mother". Since Audre Lorde said "we can learn to mother ourselves," I believe that MaComere means the way we learn to mother ourselves together.

It is no coincidence that this journal came yesterday in the midst of a period (surrounding Mother's Day) where J and I are struggling with how our relationships to our mothers and their challenges and our difficult memories of their frequent desperation impact each of us and our relationships to each other. It is not a coincidence that this came on a day that I was blessed to sit and talk about how/if we can remember what our grandmothers know with sisters who have been partners with me in the creation of UBUNTU arts--- a comothering process of nuturing, healing, and making space that has forever transformed me. It is no coincidence that J needed a little mothering in the minutes before the package arrived.

And indeed it is divine that the piece I wrote, a blue airmail letter between myself and my mother and grandmother, between myself and the Caribbean women writers and scholars who have made me possible, between myself and the mother daughter granddaughter characters of Dionne Brand's novel At the Full and Change of the Moon, with footnotes full of overdue shout-outs to my fellow travelers in a graduate seminar on Negritude arrived when it did . Two full years after the scheduled publication...but you know...Caribbean time stretches to dream for those of us living dispersed.

I'm honored that my piece appears after (or anywhere near!) a poem called "Hook"

by Olive Senior (THE Olive Senior) about mother's and daughters trying to catch each other through letters and clothing and loss. It is a miracle that my work appears alongside work by Olive Senior and Pamela Mordecai and Ramabai Espinet women whose books sit on my shelf, who I studied for my prelim exams who make me cry and think about everything differently when I hear them read outloud. Women who have been helping me mother myself even if they don't know it.

And it is no coincidence that you are reading this on a blog that is made worthwhile for me by the reading eyes and open hearts of everyone, but especially radical womyn of color comothers with me in a transformed world.

Thank the Lorde for comothering and the possibility of being reborn together. (And thank you!)

Check out the journal here: http://www.macomerejournal.com/issues/008.html

love,

lex

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Freedom Dreams: Blog About Palestine Day

This week thanks to some precious advice from Fallon Wilson I have started remembering and recording my dreams.

This is a scene from a dream I remembered on Monday morning:

"and then i met a dark man with a beard. committed to defending the olive trees to the death. but he told me, unashamed, that he would never harm the woman i named, even if she ate every olive."

This affirms what I already know. A free Palestine is an imperative in my life time. The occupation that outlived June Jordan will not survive us. Period.

I think this dream was probably also influenced by what a learned at a progressive and belated passover sader that I was able to attend a couple of weeks ago...which was some insight into the profound impact of the Isreali uprooting of olive trees in Palestine. A friend explained to me that there is no equivalent that explains how important the olive trees and the olives themselves are to the survival, culture, heritage and well being and sustainability of the Palestinian people. I now understand that the uprooting of these olive trees is a violence against the earth and a deep harm to humanity. I remember that I learned to read in Spanish against the backdrop of Lorca's screams about arboles de aceituna. I remember that olive trees are one of the major metaphors in the bible, a teaching tool about what heritage is, about how our actions impact generations. Maybe I should go back and read those parts.

Maybe I was the dark bearded man in the dream. He was ready to die. I think he was ready to kill too. But I asked him about a particular woman (i don't know or remember who) and he said even she ate every olive he would do no violence.

There is something for me to learn here about the relationship between the fruit and the roots. I am being reminded that there is a difference between the cause and the manifestation of violence. I am being reminded to be radical. I am being reminded to go for the root. I am being reminded that there is a place for forgiveness in militancy. I am being reminded that our sustainability is worth more than our individual lives.

I am being reminded to grow.

I am free when Palestine is

love,

lex

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

There is Such a Thing as Growth

or because this made me cry.

Vita's Garden

by K Shalini

http://www.thedoorpost.com/?film=5687a4a5d7688f30a41c08565a23d5b2

Shalini also has another film about the importance of water:

A Drop of Life

http://www.adropoflife.tv/

And check out OUR garden! www.ubuntugrows.blogspot.com

Monday, May 05, 2008

Lest We Forget: Radical Black Feminism Defined

Friday, April 25, 2008

Bell Defined (for Sean and all of us): 4/25/2008

Bell. Defined.

that dark thing

sometimes golden

sometimes bright

heavy

round

breakable

that dark thing

sometimes shining

sometimes waiting

sometimes broken and rusted

that heavy something

that does it's only job

regularly

brutally clear

that invention

simple instrument

breakable

sometimes bronze

heavy like morning

jarring like wake up

that heavy open metal

that furnace fused curve

thick skirt to hide

under

that shape of birthing

as iron as chains

that heavy open metal

that alarm

that sound

that sound

that again

again

again

that thing

that deep and elevated symbol

in the middle of the town square

that

that reminds the people

what they know

time to

get up

up

get up

again

brutally clear job of waking

bell

that thing that reminds us

what time it is.

-alexis pauline gumbs

April 25th, 2008

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Always Always: (Breast) Cancer and Black Queer Futurity

Hey all,

Hey all,This is the talk I gave at the Race, Sex and Power Conference in Chicago on April 12th. I was really excited for the opportunity to talk about something so important and so silenced in our communities. It is something that impacts my family directly, and which is not really addressed in my dissertation. Creating this talk makes me want to think about the queer future of this set of thoughts...so feedback would be especially welcomed here.

love,

lex

Always Always;

(Breast) Cancer and Black Queer Futurity

dedicated to Diane and Kyla

I.

It means you are terrified of love. This is what June Jordan said about living with her 40% prognosis of survival with breast cancer. It means you are terrified of love. It means all references to future time leave you feeling/ignored or irrelevant or both. It means death is always always/blurring your vision with tears. Two weeks ago I looked at June Jordan’s original handwritten drafts of this speech, the Keynote for the Mayor’s Summit on Breast Cancer in San Francisco in November 1996. I wanted to see if she had revised it, if maybe she had described it that way on second thought. I was hoping that maybe she didn’t really feel that way, not on the top of her head, not in the memory of her hand. I sat in the archive hoping that “always always” was a revision. A performative poetic effect for the audience, if not a typo. But there it was, and this time my vision was blurred. In somewhat shaky cursive, in blue ink on legal paper and then again in both typewritten versions. It means death is always always blurring your vision with tears.

I know that starting here endangers my ability to read the talk, but this is the only place to start. This is not about some smart thing that I should say before someone else says it. This is not about some abstract idea that gains me social capital in an academic market. This is not an excerpt from a chapter of my dissertation. This is about people I love, who are living and people who I love who are here even though they are not. I think this about someone who you still love too. This is about what it means that death is always, always blurring our vision with tears. That our chances of survival are less than half.

I believe that by pausing for a moment on June Jordan and Audre Lorde’s understandings of their own journeys, surviving and then not surviving breast cancer we can learn to have a discussion about black relationships, futures, bodies and possibilities that we cannot have if we do not pause here. Please pause with me for a moment here, take a deep breath and remember the name of someone whose spirit comes into the room whenever we talk about the impact of breast cancer on all of our communities.

II.

Imagine that we are having a conversation right now. About queer life and death, about black queer folks, about disease, about dying, about loving, about death blurring our futures. There is more than a 50% chance, maybe more like a 70% chance that we are having a conversation about HIV/AIDS right now. And we need to talk about HIV/AIDS. If talking about HIV/AIDS every single day will save our youth, will teach us how to embrace our loved ones who are living and no longer living with this epidemic we need to talk about it everyday. 3 times a day. We need that conversation like we need food. 5 times a day. We need that conversation like we need prayer. As I am sure at least one of my co-presenters will mention, we need to talk about HIV/AIDS because its impact on our communities shows us how interconnected we all are, through love, the sex, through birth, through knowledge. The discourse on HIV/AIDS teaches us something very important about what we transmit and how through, with and as community.

But a disease does not have to be sexually transmitted or contagious at all to remind us how much we need each other, how much we want each other, how much we come from each other. Our supposedly individual bodies do not end at our skin, or our fingertips or at any of our mucous membranes. Desire reaches out past those boundaries. Which is why we are terrified of love, which is why death is always always blurring...

Consider what June Jordan says ran across her mind when she first heard her doctor announce the “bad news” that would ultimately be her breast cancer diagnosis:

“Had something god-awful happened to my son? My lover? One of my students?”

June Jordan said this, in the doctor’s office, waking up from anesthesia after a biopsy. The whole scene was designed to analyze her individual body and its likelihood to survive or whither away, but the first question was about if something “god awful” had happened to the people she was connected to through love. And unfortunately, the answer was yes. Something had happened to her son, her love, every one of her students. Something god-awful. His mother, her lover, their teacher was about to know that she was more likely to die than to survive. Her body was about to be changed forever which meant none of them, none of us could ever be the same. This is exactly why we are terrified of love. This is why death is always always blurring our vision with tears.

If we remember that June Jordan and Audre Lorde were mentors and teachers to our black queer heroes, Essex Hemphill, Melvin Dixon and many many more we will understand that breast cancer is something that happened, in advance, to a black gay movement, and HIV/AIDS is something that happened to June Jordan and Audre Lorde as they became historicized as queer anscestors. This is the importance of the phrase “always always”. The timing of death, especially the queer timing of black death and the deadly timing of queer black futures means death is always always blurring our vision. And blinking doesn’t fix it.

What I am trying to do here, or what I am asking for from you, is an always always timing, inspired by Audre Lorde and June Jordan where we can understand, our lives, our loves, our connections, our bodies, our cells, our traps, our freedom in all directions, out and in towards hope.

III.

On November 19th 1979 Audre Lorde wrote in her journal “We have been sad long enough to make this earth either weep or grow fertile. I am an anachronism, a sport, like the bee that was never meant to fly. Science said so. I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation. But I do live. The bee flies. There must be some way to integrate death into living, neither ignoring it nor giving in to it.”

In November 1979 Audre Lorde wrote this in her journal. “I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body....”. November 1979 was not just any time to have written this statement about how death and life live here in our bodies (always always blurring as Jordan would say) Lorde individually was healing from her radical masectomy when she wrote this, fighting cancer day by day, but the death she was holding in her body was not merely individual. November 1979 was the fall when in Atlanta black children started disappearing. Small black bodies turned up in ravines. Elementary school students lost deskmates and friends. Everyone was afraid to walk home alone. Little black children had to wear the reality, “I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation.” Audre Lorde’s former colleague from the SEEK minority education program at the City University of New York Toni Cade Bambara, who we also lost to cancer, was living in Atlanta, with her 10 year old daughter, writing a book that she would never finish, a book that she would never stop writing Those Bones Are Not My Child. “I carry death around in my body like a condemnation.” By 1979 Ronald Reagan has already coined the term “welfare queen”, Moynihan and his interpreters have already confirmed that black maternity is a disease plaguing our cities. “I carry death around in my body, like a condemnation.”

Just months earlier, at the beginning of 1979, in the black neighborhoods in Boston 12 women were killed, their bodies showed up floating, or grounded in the morning. Audre Lorde had worked consistently with the Boston-based Combahee River Collective. Barbara Smith sent her every clipping about every woman who had been killed, even though most of the news coverage blamed the victims. What were they doing out at night? They must have been prostitutes. Their deaths are not noteworthy. Many of the murders did not even make the news. “I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation.”

As both Audre Lorde and June Jordan repeated again and again in their writing about surviving breast cancer, diseases are not individual things, they exist in a social matrix. Thus Jordan’s anger about the deprioritization of breast cancer, which she believed was due to the fact that the disease was associated with women and women’s lives were undervalued in the medical industry. And thus Lorde’s discussion of the way women who had undergone masectomies were so strongly encouraged to use prosthetic breasts and implants even when it wasn’t in the best interest of their health, because, as Lorde points out...a woman’s body is simply something to look at. In both cases Jordan and Lorde are crying out against the fact that the pain black women experience is supposed to be silenced, is supposed to be covered over. And they both refused, and since their words are still here they still refuse. When Audre Lorde and June Jordan talk about breast cancer they are not only talking about breast cancer they are battling a larger understanding of social death mapped onto the bodies of black people, and queer black people in particular. Audre Lorde said “the enormity of our task, to turn the world around. It feels like turning my life around, inside out.”

IV.

And lest my argument about how these individual deaths are about everyone seem too normalizing, let me emphasize that what I am talking about is a queer experience, where queer means a relationship to time that is not the reproduction of the same, where queer means a violent disjuncture between how our bodies are interpreted by the outside world and how we feel inside them, where queer means “I am not supposed to exist,” but I do. In that sense, most of the black people on this planet are having a queer experience right now. Listen to the way Audre Lorde describes the experience of anesthesia just following her surgery: “Being ‘out’ really means only that you can’t answer back or protect yourself from what you are absorbing through your ears and other senses.” Listen to the way she describes her body as she heals: “I feel always tender in the wrong places.” The surgical experience, the experience of dealing with a body that is understood to be “diseased” is a queer experience. We are tender in what are thought to be the wrong places. And again this is not simply to say individuals who experience extreme health difficulties are queer individuals, it is to say that our whole relationship to death and living as black folks, as folks who are called sexually deviant, as folks creating family out of struggle is a queer relationship. We think that we are over death, but we are not. We are “always tender in the wrong places.” We can’t answer back. We can’t protect ourselves.”