Hey all,

This is the talk I gave at the Race, Sex and Power Conference in Chicago on April 12th. I was really excited for the opportunity to talk about something so important and so silenced in our communities. It is something that impacts my family directly, and which is not really addressed in my dissertation. Creating this talk makes me want to think about the queer future of this set of thoughts...so feedback would be especially welcomed here.

love,

lex

Always Always;

(Breast) Cancer and Black Queer Futurity

dedicated to Diane and Kyla

I.

It means you are terrified of love. This is what June Jordan said about living with her 40% prognosis of survival with breast cancer. It means you are terrified of love. It means all references to future time leave you feeling/ignored or irrelevant or both. It means death is always always/blurring your vision with tears. Two weeks ago I looked at June Jordan’s original handwritten drafts of this speech, the Keynote for the Mayor’s Summit on Breast Cancer in San Francisco in November 1996. I wanted to see if she had revised it, if maybe she had described it that way on second thought. I was hoping that maybe she didn’t really feel that way, not on the top of her head, not in the memory of her hand. I sat in the archive hoping that “always always” was a revision. A performative poetic effect for the audience, if not a typo. But there it was, and this time my vision was blurred. In somewhat shaky cursive, in blue ink on legal paper and then again in both typewritten versions. It means death is always always blurring your vision with tears.

I know that starting here endangers my ability to read the talk, but this is the only place to start. This is not about some smart thing that I should say before someone else says it. This is not about some abstract idea that gains me social capital in an academic market. This is not an excerpt from a chapter of my dissertation. This is about people I love, who are living and people who I love who are here even though they are not. I think this about someone who you still love too. This is about what it means that death is always, always blurring our vision with tears. That our chances of survival are less than half.

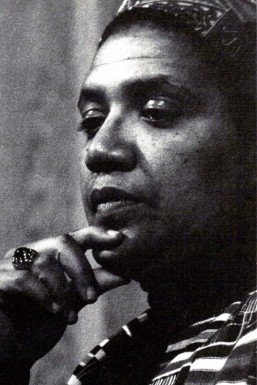

I believe that by pausing for a moment on June Jordan and Audre Lorde’s understandings of their own journeys, surviving and then not surviving breast cancer we can learn to have a discussion about black relationships, futures, bodies and possibilities that we cannot have if we do not pause here. Please pause with me for a moment here, take a deep breath and remember the name of someone whose spirit comes into the room whenever we talk about the impact of breast cancer on all of our communities.

II.

Imagine that we are having a conversation right now. About queer life and death, about black queer folks, about disease, about dying, about loving, about death blurring our futures. There is more than a 50% chance, maybe more like a 70% chance that we are having a conversation about HIV/AIDS right now. And we need to talk about HIV/AIDS. If talking about HIV/AIDS every single day will save our youth, will teach us how to embrace our loved ones who are living and no longer living with this epidemic we need to talk about it everyday. 3 times a day. We need that conversation like we need food. 5 times a day. We need that conversation like we need prayer. As I am sure at least one of my co-presenters will mention, we need to talk about HIV/AIDS because its impact on our communities shows us how interconnected we all are, through love, the sex, through birth, through knowledge. The discourse on HIV/AIDS teaches us something very important about what we transmit and how through, with and as community.

But a disease does not have to be sexually transmitted or contagious at all to remind us how much we need each other, how much we want each other, how much we come from each other. Our supposedly individual bodies do not end at our skin, or our fingertips or at any of our mucous membranes. Desire reaches out past those boundaries. Which is why we are terrified of love, which is why death is always always blurring...

Consider what June Jordan says ran across her mind when she first heard her doctor announce the “bad news” that would ultimately be her breast cancer diagnosis:

“Had something god-awful happened to my son? My lover? One of my students?”

June Jordan said this, in the doctor’s office, waking up from anesthesia after a biopsy. The whole scene was designed to analyze her individual body and its likelihood to survive or whither away, but the first question was about if something “god awful” had happened to the people she was connected to through love. And unfortunately, the answer was yes. Something had happened to her son, her love, every one of her students. Something god-awful. His mother, her lover, their teacher was about to know that she was more likely to die than to survive. Her body was about to be changed forever which meant none of them, none of us could ever be the same. This is exactly why we are terrified of love. This is why death is always always blurring our vision with tears.

If we remember that June Jordan and Audre Lorde were mentors and teachers to our black queer heroes, Essex Hemphill, Melvin Dixon and many many more we will understand that breast cancer is something that happened, in advance, to a black gay movement, and HIV/AIDS is something that happened to June Jordan and Audre Lorde as they became historicized as queer anscestors. This is the importance of the phrase “always always”. The timing of death, especially the queer timing of black death and the deadly timing of queer black futures means death is always always blurring our vision. And blinking doesn’t fix it.

What I am trying to do here, or what I am asking for from you, is an always always timing, inspired by Audre Lorde and June Jordan where we can understand, our lives, our loves, our connections, our bodies, our cells, our traps, our freedom in all directions, out and in towards hope.

III.

On November 19th 1979 Audre Lorde wrote in her journal “We have been sad long enough to make this earth either weep or grow fertile. I am an anachronism, a sport, like the bee that was never meant to fly. Science said so. I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation. But I do live. The bee flies. There must be some way to integrate death into living, neither ignoring it nor giving in to it.”

In November 1979 Audre Lorde wrote this in her journal. “I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body....”. November 1979 was not just any time to have written this statement about how death and life live here in our bodies (always always blurring as Jordan would say) Lorde individually was healing from her radical masectomy when she wrote this, fighting cancer day by day, but the death she was holding in her body was not merely individual. November 1979 was the fall when in Atlanta black children started disappearing. Small black bodies turned up in ravines. Elementary school students lost deskmates and friends. Everyone was afraid to walk home alone. Little black children had to wear the reality, “I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation.” Audre Lorde’s former colleague from the SEEK minority education program at the City University of New York Toni Cade Bambara, who we also lost to cancer, was living in Atlanta, with her 10 year old daughter, writing a book that she would never finish, a book that she would never stop writing Those Bones Are Not My Child. “I carry death around in my body like a condemnation.” By 1979 Ronald Reagan has already coined the term “welfare queen”, Moynihan and his interpreters have already confirmed that black maternity is a disease plaguing our cities. “I carry death around in my body, like a condemnation.”

Just months earlier, at the beginning of 1979, in the black neighborhoods in Boston 12 women were killed, their bodies showed up floating, or grounded in the morning. Audre Lorde had worked consistently with the Boston-based Combahee River Collective. Barbara Smith sent her every clipping about every woman who had been killed, even though most of the news coverage blamed the victims. What were they doing out at night? They must have been prostitutes. Their deaths are not noteworthy. Many of the murders did not even make the news. “I am not supposed to exist. I carry death around in my body like a condemnation.”

As both Audre Lorde and June Jordan repeated again and again in their writing about surviving breast cancer, diseases are not individual things, they exist in a social matrix. Thus Jordan’s anger about the deprioritization of breast cancer, which she believed was due to the fact that the disease was associated with women and women’s lives were undervalued in the medical industry. And thus Lorde’s discussion of the way women who had undergone masectomies were so strongly encouraged to use prosthetic breasts and implants even when it wasn’t in the best interest of their health, because, as Lorde points out...a woman’s body is simply something to look at. In both cases Jordan and Lorde are crying out against the fact that the pain black women experience is supposed to be silenced, is supposed to be covered over. And they both refused, and since their words are still here they still refuse. When Audre Lorde and June Jordan talk about breast cancer they are not only talking about breast cancer they are battling a larger understanding of social death mapped onto the bodies of black people, and queer black people in particular. Audre Lorde said “the enormity of our task, to turn the world around. It feels like turning my life around, inside out.”

IV.

And lest my argument about how these individual deaths are about everyone seem too normalizing, let me emphasize that what I am talking about is a queer experience, where queer means a relationship to time that is not the reproduction of the same, where queer means a violent disjuncture between how our bodies are interpreted by the outside world and how we feel inside them, where queer means “I am not supposed to exist,” but I do. In that sense, most of the black people on this planet are having a queer experience right now. Listen to the way Audre Lorde describes the experience of anesthesia just following her surgery: “Being ‘out’ really means only that you can’t answer back or protect yourself from what you are absorbing through your ears and other senses.” Listen to the way she describes her body as she heals: “I feel always tender in the wrong places.” The surgical experience, the experience of dealing with a body that is understood to be “diseased” is a queer experience. We are tender in what are thought to be the wrong places. And again this is not simply to say individuals who experience extreme health difficulties are queer individuals, it is to say that our whole relationship to death and living as black folks, as folks who are called sexually deviant, as folks creating family out of struggle is a queer relationship. We think that we are over death, but we are not. We are “always tender in the wrong places.” We can’t answer back. We can’t protect ourselves.”

And we are always tender in the wrong places because we are interconnected, we are always touching. And while reading and knowing of Audre Lorde’s battle with breast cancer which eventually metastisized is devastating, alongside, or actually inside the story of that loss is the story of the network. In the I, Lorde describes the network of chosen family that “sprung into gear” to help her and her family with healing. Later in 1992 when her cancer finally spread everywhere, former student asha bandele told me how she was there, organizing, comforting, planning with Audre Lorde while she transitioned. While painstakingly reading through June Jordan’s medical records last month I was shocked by the pain and deterioration she experienced and by what seemed like cruelty on the part of insurance officials and medical providers towards the end of Jordan’s life. But I was also struck by the network of former students, friends and colleagues who gathered to take care of Jordan. To watch after her pets, to deal with her plants and her papers, to battle the University of California which it seemed almost needed proof that she was dead to grant her medical leave. People took shifts and worked around the clock to make it clear that the process of living and the process of transition for Jordan was not an individual situation, it was a community activity.

And more recently more personally Mama Nayo Barbara Watkins, a cultural worker, organizer and visionary who was my age during the black arts movement in the south, who used poetry to register people to vote and who raised 8 children mostly by herself, Mama Nayo who became an ancestor January 29th of this year, called on my community, a set of chosen daughters to be with her. I sat beside her and read my students’ final projects in her ear while she dozed. I sat and held her hand while her grandchildren played around on the floor. I adjusted neck pillows. I watched hours of CNN (the ultimate act of love...especially at that point during the primary season). We fed the dog, enlisted people all over our community to make soup, we read out loud a lot. We sang. We held her grown up children and growing grandchildren while they cried. We sang and danced with intensity to send Mama Nayo all the way home, which is someplace from which she still speaks to us. I know that ending my paper here is a risk that everything will blur with tears. And every time, I think I have it together...I still fall apart. I am always tender in the wrong places.

V.

Unresolved. Love is a queer thing. Death is a queer thing too. Audre Lorde tells us that “the only answer to death is the heat and confusion of living.” May we be hot and confused, may we be incomprehensible and held. May we be open, and unready. May we be surprised and waiting and hopeful. May we be singing in our loss, muscular in our grief, may we be whoever we need to be for the threatened miracle of each other. This is for June, this is for Audre, this is for Toni, this is for Mama Nayo, this is for Diane, this is for Kyla, this is for you who are listening in your bodies and in the air. Always. Always. Thank you.